Almost a decade ago, we enlisted the kids’ help to keep careful tabs on the temperature of the Thanksgiving turkey as it was roasting. We roasted a 24 pound, unstuffed turkey from a local farm (all natural, no “solutions” injected in to it, and minimally processed) at a constant temperature of “325” F – that is what the oven dial was set to, at any rate. We used a thermometer with a probe connected to a digital display – this type of thermometer allows you to run this experiment while making only one puncture in the turkey. The turkey started cooking at 40 degrees.

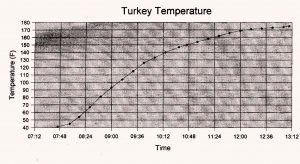

As you can see from this graph, it took about 6 hours to bring the roast from 40 degrees to 175. The temperature rose quite quickly for the first 4 hours, then the change in temperature slowed down considerably.

This experiment, and subsequent discussions with scientists, gave us a greater understanding of the Thanksgiving paradox: as the turkey gets closer and closer to being done it never seems to be done. After several hours, as the house fills with the good smell of roast turkey, the recalcitrant turkey sits there with the thermometer showing clearly that it is not yet cooked. We always start to wonder if the oven has gone out or if the oven thermostat has ceased working. We shake the drumstick, we poke the turkey, we open the oven way too many times, putting a hand in to see if it still feels hot etc. Why do we do this, year after year – with the Thanksgiving turkey, a Christmas roast beef, and any other large piece of roasting meat?

I spoke with a well-known astrophysicist, to try to get some answers. He says people tend to view trends as linear processes, so they will see the temperature rising quickly at the beginning, assume that this quick trend will continue at the same rate, and feel that the turkey should be done much earlier than it really will be. He says in fact “the plot above is a solution of a well-known heat diffusion equation* which applies to all cooking processes with the exception of microwaves.” The steepness of the line in the curve is a measure of the heating rate of the turkey. The heating rate (the change in temperature in a particular time) is proportional to the change in temperature between the turkey and the oven. The temperature of the turkey will approach, but never reach, the temperature of the oven. As the turkey gets warmer, the temperature change in an hour decreases (it goes up, but less quickly).

The astrophysicist, who likes to simplify problems so they can be solved, says you can “view the turkey as a solid,” “assume a spherical turkey” and “assume a non-spherical turkey.” He then considered the problem of cooking stuffed turkeys vs. unstuffed turkeys, the stuffed turkey being closer to a spherical turkey and the unstuffed turkey having an empty cavity which reduces the thickness of the material to be cooked and effectively reduces the size of the turkey. The concept of a spherical turkey provoked a lot of laughs, but in the real world, there are no spherical turkeys. Real turkeys have wings and drumsticks.

He provided a helpful reference to The Science of Cooking, by Peter Barham, which notes “… the cooking time is always proportional to the square of the size of the food, rather than its weight.” You can understand this if you consider that the same weight of turkey, cut in to pieces, will cook in much less time than the same exact turkey cooked whole.

This is why chefs will tell you to cut the turkey up in pieces, roasting the light meat and dark meat for different amounts of time so that the light meat does not become dry and the dark meat gets more time in the oven. However, the “dissected turkey” method of cooking the Thanksgiving turkey is impractical for those cooks who want to present a Norman Rockwell turkey (visually appealing whole turkey on a platter) at the table. The Norman Rockwell turkey requires compromises, and more time than you may think.

*the solution of the heat diffusion equation is an exponential process, if you extrapolate a line from the early cooking temperature data you will expect the turkey to be cooked many hours sooner than when it is actually cooked.

26

“… the cooking time is always proportional to the square of the size of the food, rather than its weight.”

How is he defining “size” – the linear dimension, the volume?

What shape is assumed?

P.S. Might mention the classic, http://www.amazon.com/Consider-Spherical-Cow-John-Harte/dp/093570258X#reader_093570258X

Excellent point. Cooking time depends on the distance of the meat from the hot air in the oven, so the length in question is the thickest part of the turkey. Of course we can’t speak for Mr. Barham, who is quoted there, but size in this case would be thickness. For an un-stuffed turkey, the critical thickness is the thickest part, often near the leg joints. The result of roasting the turkey as a whole unit is that compromises on cooking time will be required so that the thickest parts will be fully cooked, resulting in the thinner portions being overcooked. We were only assuming a spherical turkey when it was stuffed. When it is not stuffed, you can assume it is a spherical shell, with a thickness equal to the thickest part of the turkey.

This does not, however, address the key debate question of whether the stuffing should be cooked inside the turkey or in a separate dish, which would require extensive study and perhaps several experiments……